MENA Regierungen tun zu wenig gegen weibliche Genitalverstümmelung (FGM)

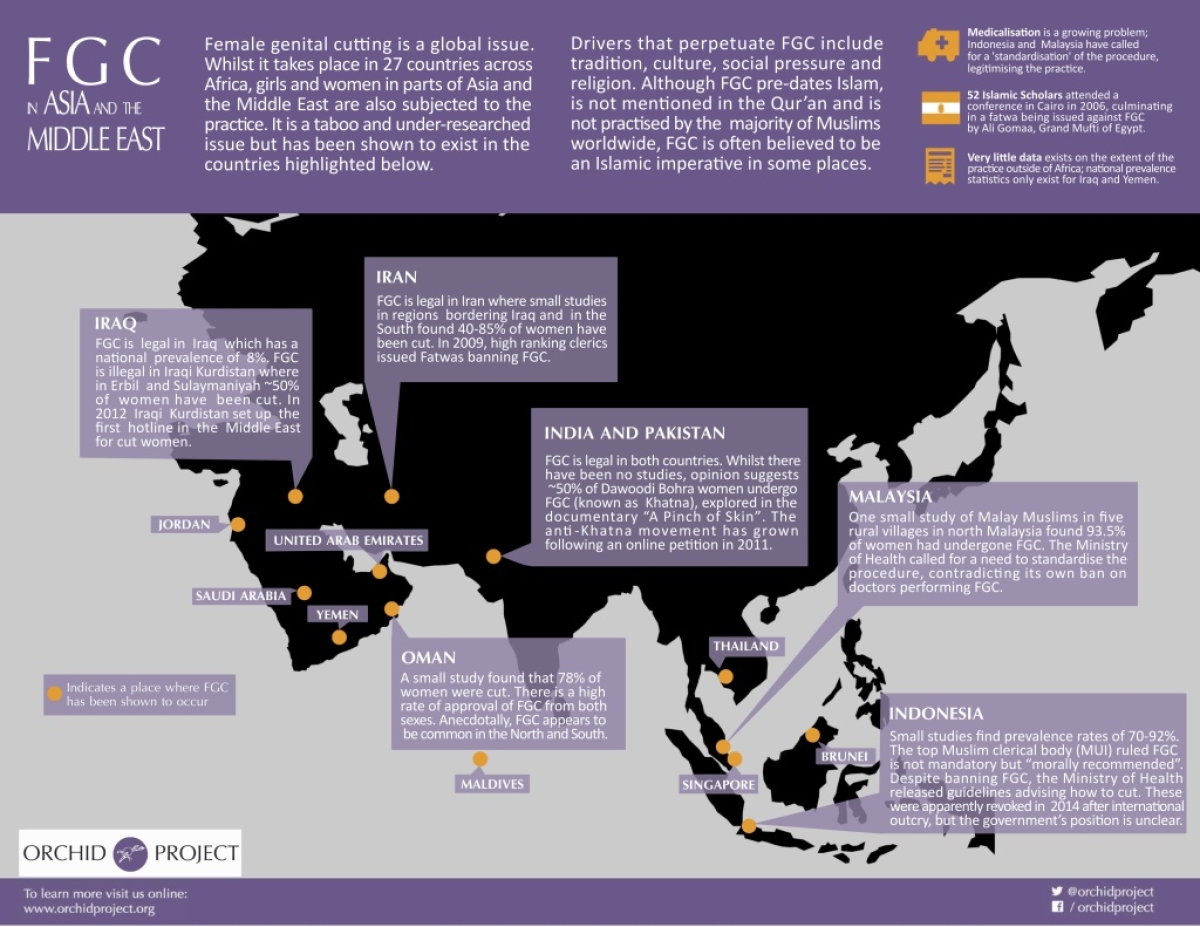

Noch immer gilt weibliche Genitalverstümmelung (FGM) vornehmlich als "afrikanisches Problem" selbst wenn in den letzten Jahren aus immer mehr Ländern im Nahen Osten und Zentral- wie Südostasiens Daten belegen, dass auch hier diese Praxis weit verbreitet ist.

Nur in wenigen Staaten ist FGM gesetzlich verboten, in Irakisch-Kurdistan seit 2011 im Oman seit wenigen Jahren. In einem Artikel für den New Arab kritisiert Paleki Ayang von Equality Now in scharfen Worten, wie wenig bislang in der Region gegen FGM unternommen wurde:

“The growing weight of evidence demonstrates the urgent need to accelerate efforts to end FGM. Every day, girls are being subjected to the traumatising practice without anywhere to turn for protection and no access to support or legal recourse in the aftermath.

Only five MENA countries have anti-FGM laws, namely Egypt, Oman, Sudan, Yemen, and Iraq, where anti-FGM legislation only applies to the Kurdistan region. Of these, all apart from Oman have provide nationally representative data on FGM that shows that despite its illegality, FGM continues to be widely practiced.

Countries making little efforts to end this harmful practice include Iran, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. None have specific laws prohibiting FGM, and this coincides with a lack of large-scale data. Only smaller studies and anecdotal evidence are available, making it difficult for activists and civil society to pressure governments to pass legislation or commit resources towards combating this harmful practice.

FGM is conducted both by native populations and migrant communities, which carry the tradition to other countries. To address this, efforts to tackle FGM need to be collective and coordinated amongst MENA countries, as well as across countries globally where it is perpetuated by some in the diaspora. (…)

A new study by the Tadwein Centre for Gender Studies found 86% of underprivileged women aged 18 to 35 in Egypt had undergone FGM, just 1% less than in 2014, when Egypt released its last National Health Survey.

However, some progress in shifting public opinion has been made; there has been a drop in support for FGM, with only 38.5% of women and 58% of men agreeing with its continuation. Previously, the figure was around 50% amongst women.

It’s time MENA governments live up to their international human rights commitments to protect women and girls from FGM. This means acknowledging it is happening in their countries, collecting national-level data, passing laws that criminalise FGM and investing resources in prevention and protection.

To end FGM, holistic, multi-sectoral action plans are required, including a widespread awareness-raising programs that help communities to abandon FGM as a serious human rights violation and form of violence against women and girls that must end.”